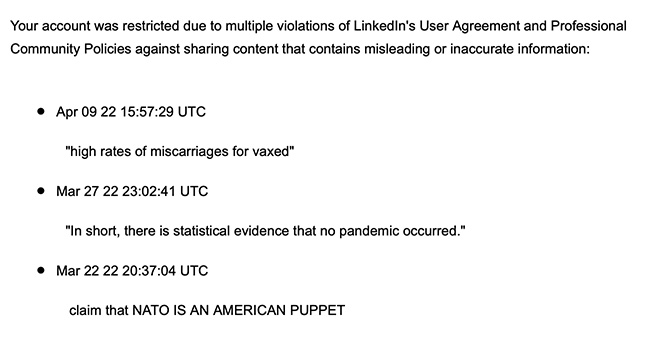

Michael Reichel, a Swedish entrepreneur, reveals how LinkedIn staff monitors and interferes with private communications between LinkedIn members. It started after Reichel expressed critical opinions on the platform about NATO and covid. This resulted in LinkedIn staff investigating Reichel’s interactions with other members.

By Michael Reichel, Sweden

I became a member on LinkedIn in 2006, only three years after when Reid Hoffman and Eric Ly founded this business network. Having been one of the early adopters of the Internet, I joined several IRCs and bulletin boards that allowed simple text-based conversation long before the world wide web was available. This was in the late 80s.

Hence, when LinkedIn arrived on the scene, I joined, and so did most of my business contacts around the globe. For me, it became the prime means for not as much making new friends but to retain contact beyond the profession. All resulting in rather good discussions on a broad range of subjects.

My house rule was to not fall for the Facebook bug and “make friends” with anyone that wanted to grow their network, my friends I already knew in one capacity or the other.

Perhaps this influenced the quality of the discourse, and it had more etiquette, professionalism, brains, and stringency to the subjects than alternative social networks had. That has been important to me and is why I rarely visit Facebook.

The motor in LinkedIn’s business engine is the users, people like you and me. Today, there are more than 774 million users (source Wikipedia). With us in the same space, we are exposed to a range of monetizing schemes. One of them is advertising. Another is data mining, and profits from this they make too.

Already after three years after the start, of 2006, they made financial breakeven and a year later broke the 10 million user barrier. Not surprisingly, its investors wanted returns, and an IPO happened in 2011. Another five years later, Microsoft became the owner of one of the largest acquisitions Microsoft ever made. So, it must have been important to them, perhaps not for what it did but for what it may do.

Following a series of acquisitions, the range of services embedded in LinkedIn grew. They are advanced and complex and not so much about making it better for the individual user but providing “value-added” services to paying users, predominantly businesses. LinkedIn has become a prime platform for business-to-business marketing. LinkedIn, for better or worse, is far from what it was back in 2006 as its revenues are from corporations.

Herein lies the conundrum. How to protect what it has become, to become dependent on the source of the gravy and less on universal values.

This brings us to a subject of great interest to me, when does a private company become so influential that its ethos attains ethical responsibility? In other words, how may such an influential entity use its powers?

What powers, you may ask?

The power of control of information. With access to 774 million eyes, ears, and minds that are not just average Joe and Jane but active in global businesses, you are at the top of the influencer league, hands down.

Just to get you going, the World Economic Forum [WEF] appears to be spending an impressive share of their communication budget on LinkedIn. Guess why?

As a baseline, before getting into that, let’s just visit LinkedIn’s terms and conditions as a user. More specifically, you must not be “misleading or inaccurate.” Ah, the truth! I can do that! That sounds like a great deal!

And I did… but look what happened, the first time my account was suspended, I managed to establish a good exchange with an actual person (or was it an AI) because I was lucky to prove my statements to be not misleading and actually entirely accurate. I got Linkedin to eat their own dog food, so to speak. Thus, I got back in the saddle, but only after promising not to be misleading and inaccurate. Really!

Let’s pause shortly and make a reality check. Perhaps you have seen the WEF ads on LinkedIn? How accurate and not misleading are they? The payback is in reading the comments. Clearly, there is hope for mankind.

Aware they now had their eyes (or AI) on me, I became even more cautious before making any statements that may be construed as misleading or inaccurate. By now, you may be thinking, “This guy does not get it. It is not about that”. That is a good point, and you are right. This is a prime example of gaslighting, an attempt to change my behavior to self-censor, to accept and follow a narrative. The purpose is to rattle or question my foundation of values and to force me in line with “the others”. There is a term for this, too, social engineering.

It does not end there. Most democratic constitutions hail the freedom of speech as one of the core pillars of democracy. LinkedIn uses its powers to not just not abide to this elementary value but to ensure a certain narrative prevails.

Hence, rather than supporting democratic principles, LinkedIn is actively acting anti-democratically. There are no ifs, and´s or but´s here, this is what they are doing, and they are doing it under the false pretext of a desire not to be misleading or inaccurate (the gaslight). Who are they to judge? Well for one thing there is an entire department involved in playing God here. That is, to assume the privilege of interpretation of what will be the accepted “truth.”

For such a department to function, there have to be work instructions, and this is where the problems arise. It is the contributing members’ open discourse itself that should distill or reach what may be deemed accurate and not misleading. The moment you intervene and censor is the instance it all falls apart.

“I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it” – Voltaire

“In times of deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act” – George Orwell

But there is more, and it is worse, much worse.

LinkedIn staff intercepted private member communications in order to deplatform user

LinkedIn offers a messaging system, much like Facebook’s “Messenger” so that you may have private conversations without resorting to other methods such as email, Signal, and so on. The premium version you have to pay for.

One of my followers wrote this to me;

“Your messages to me were blinded and marked with this message; If the content in this message is unwanted or harmful, please report it to us. We won’t notify the sender.

It’s bad enough that they want to block your page and posts, but to tell me that private messages I have read from you may be unwanted or harmful (as if I can’t make that decision for myself) is insulting and feels like a violation of my privacy.”

My heart warms with this person’s good values and courage.

There we are. LinkedIn takes its lack of morals and goes further by monitoring private communication. To top off the transgression, they evidently solicit and encourage such a party to become an informer (nark) for the purpose of building a case against the person they have targeted.

The last time I heard about such methods was in totalitarian and communist states like former East Germany and Pol Po’s Cambodia. Then, the “we won’t notify the sender” is a technique to push the subject to be morally compromised.

A moment’s reflection brings up insights into how wrong all of this is, and how it weathers away the moral fabric of our society’s fundamental structures. Traditionally upholding these values is the responsibility of our politically elected representatives and also religious and academic institutions. Most of them have now succumbed to the public-private partnerships that are driven by other forces than said values.

This practice of spying on private communication is just that, espionage. It is, after all a business network and very private conversations might take place. Cui bono?

Being excluded from LinkedIn has become the mark of individuals with integrity and high standards. In fact, not only individuals but also companies and organizations too. My publisher, NewsVoice, recently rose to be a member of this no longer exclusive club. Just taken down, with no explanation. NewsVoice has been publishing for eleven years now.

The publisher’s private LinkedIn page was also taken down to add insult to injury. I guess, to be sure, his existence is properly erased.

Paradoxically for LinkedIn it has the opposite effect. It cements LinkedIn’s subversive abuse of its power. Had I been an investor in its shares, this would be a red flag. Politicizing a good business concept is simply put, foolish.

Below are screenshots of the entire conversation with LinkedIn’s Max, “Member Safety and Recovery Consultant”. The process of gaining access to an opportunity to appeal has an odd component, and you need to submit a scan of your passport. In Europe, this is a violation of the General Data Protection Act.

Many of the people that have been excluded have felt this to be such a strong violation of personal integrity that they choose not to appeal. As I don’t think the good people at LinkedIn are intellectually challenged it must be a part of the design why its lack of respect for the law is telling.

As you read my case you will see that they have not honored the promise of appeal. The door is closed. What do we call people who do not honor a promise?

On the subject of taking responsibility, one key component is not only to present yourself with a true name but to allow means for communication. LinkedIn fails here too. So, I took this to the next level and sent a letter to the only living entity that should have some ethos, a member of the board of LinkedIn Sweden.

It so happens that Tomas Frimmel is also the CEO of Microsoft Sweden. My letter was unanswered; alternative routes led me via the Microsoft PR department. The reply, via a proxy, was “no comments.” I re-asked if I understood correctly that he had no comment on the ethical dilemma in LinkedIn’s actions. The answer was “yes.”

By Michael Reichel, Sweden

Case study